After graduating with a master of divinity degree from Yale University, I was unsure what I wanted to do. I had vied for the senior pastor position at three Baptist churches, but did not succeed in getting called. I remained an associate minister at a local church, and continued as chair of the Community Outreach Committee of the Association of New Haven Clergy. I needed to find work, or an academic institution to continue on to earn a doctoral degree in some area of religious or theological studies—which I knew I would do eventually. A former theology professor I had at Yale Divinity School had guaranteed a seat for me as a doctoral student in theology, but I was not certain I wanted to pursue that area of study. I was more interested in ethics, plus I hesitated over some of the stringent requirements of graduate school at Yale, especially regarding foreign language requirements. So, I let that option fester in my mind as I sought some temporary employment.

Wanting to earn a Clinical Pastoral Education certificate that I had not sought wile a seminarian, I found a job at a facility for mildly retarded adult women (their terminology) and gained permission for the pastor of my church to oversee my progress—the end result acquiring a CPE license.

In addition, I found work as an after-school program coordinator at an Episcopal church, where I received the unofficial moniker of an associate youth minister. Whereas things were looking up in the income-earning department, I was clearly dissatisfied from directionless and unfulfilled academic or pastoral pursuits.

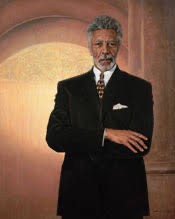

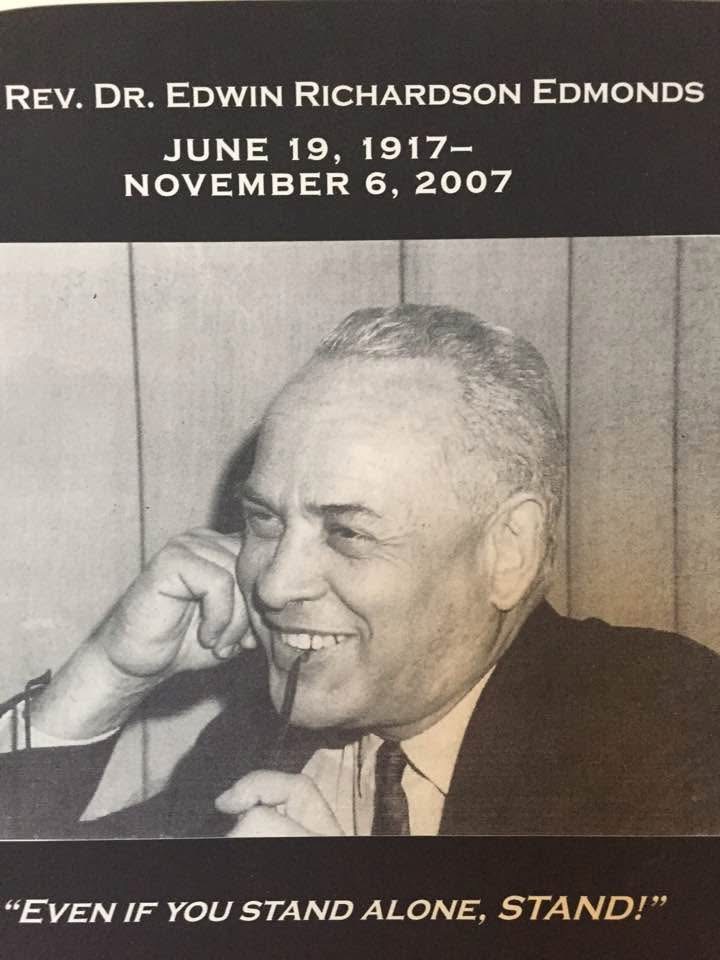

One day, I decided to go to Dixwell Avenue Community Center to see if there was any opportunity there. In the process, I was directed to visit with the Rev. Dr. Edwin R. Edmonds, the pastor of Dixwell Avenue Congregational United Church of Christ Church. He was glad I had earned my master’s degree from Yale and asked me if I might be interested in pursuing membership in the Congregational denomination. I was partially curious, albeit I had been a Baptist all of my life. He did connect me with a seasoned UCC minister to discuss possibilities, but I suspect the man detected some lack of enthusiasm in me. He did present me with some denominational paperwork that I completed, but I did not receive any follow-up from him or any denominational authority. Meanwhile, Edmonds offered me two preaching opportunities at his church while he would be on vacation in the summer. The congregation treated me well, and the experience was welcome.

What intrigued me more than Edmonds’ kindness toward me was his life story. While he was born and raised in Texas with sight, and graduated from high school at 15, his vision began to fail while he was a student at Morehouse College. His official status was legally blind, a designation often used for individuals who have some remaining vision but meet specific clinical criteria for severe impairment. Despite his visual impairment, he graduated from Morehouse in 1937, just a year later than expected, and subsequently earned a Bachelor of Sacred Theology from Boston University continued on to complete a doctorate in social ethics. While he faced “much difficulty” with visual tasks, he utilized his other skills to become an invaluable contributor in the struggle for racial justice.

Needless to say, this biographical information piqued my interest, for I was well aware that my hero, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., had graduated from B.U. with a Ph.D. in systematic theology. As we talked further, I discovered that a few professors who taught there while King was a resident student from 1951 stimulated, although I had no intention of pursuing doctoral work in systematic theology.

Subsequently, I applied to two graduate schools. One was the Illiff Scool of Theology in Denver, Colorado. That’s when I had the opportunity to speak with Dr. Vincent Harding, to whom a person in admissions transferred me, I believe, simply because I was Black! Harding did a good job of selling the school to me! It was much later that I found out Harding had greatly contributed to the speech King made at the Riverside Church officially coming out against U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War on April 4, 1967. . .exactly one year before he was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee!

The other school was Boston University, where Dr. King, Dr. Edmonds, Dr. Samuel Dewitt Proctor, and others had matriculated. B.U. had an excellent reputation for awarding the most doctoral degrees to Black students in the religious/theological area in the 1950s and 1960s! I settled on B.U. primarily because King went there; and he had put in his chapter on his “Pilgrimage to Nonviolence” in his first book, Stride Toward Freedom:The Montgomery Story, that the dean of the B.U. School of Theology, Dr. Walter George Muelder, had helped him to consider Gandhian nonviolence as a strategy to help improve the lot of Black people. Needless to say, I elected to go to B.U. to major in social ethics—which was a specialty of Muelder’s (and Edmonds’). Edmonds was one of my references, and thus easily secured my admission to its graduate program.

Despite becoming blind, Edmonds became a renowned civil rights leader and served as the pastor for 43 years at the Dixwell Avenue Congregational United Church of Christ. But prior to coming to New Haven, Edmonds was a professor of sociology at Bennett College, an historically Black institution for women in Greensboro, North Carolina. As a matter of fact, the only time Dr. King ever spoke in that city was at Bennett’s Annie Merner Pfeiffer Chapel, upon the invitation of Edmonds! King and Edmonds met in 1958 at an NAACP convention in Detroit and the two corresponded until King was slain.

Edmonds was a prominent civil rights leader in the city. He became the president of the Greensboro, North Carolina, chapter of the NAACP, and is attributed with revitalizing that chapter in 1955. He served as an adviser to the “Greensboro Four” during the 1960 sit-ins. The Greensboro Four were Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Franklin McCain, and Joseph McNeil. These young men were students at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College (NC A&T). Edmonds is recognized as a pioneer in the fight for equal rights for minorities in Greensboro.

In an reflective interview in 2004, Edmonds recounted his efforts to integrate New Haven’s schools and the discrimination he faced in the attempt to find affordable housing as well as his wife’s difficulties finding a job as a teacher. He stated that the local trade unions and the White Citizens’ Council, a coalition of businessmen, both tried to restrict African American access to jobs and job training. Edmonds appealed to Mayor Richard Lee to put pressure on these groups. This led to the establishment training programs for African Americans who wanted to learn a trade and efforts by Lee to integrate the New Haven police force. Edmonds also cofounded the group Community Progress Incorporated, which was created to organize citizens into local advisory groups who could make recommendations for community development initiatives and to lobby cooperatively for civic improvements and fixes for neighborhood problems. Edmonds also talked about the creation of Head Start in New Haven.

Edmonds, who moved to New Haven in 1959, is credited with helping to build a thriving black middle class there. When the Ford Foundation gave the city $1 million to pilot anti-poverty and job-training programs, Edmonds was appointed to the original board of the project, called Community Progress, Inc. At the time of his death in 2007 at the age of 90, he was the retired pastor of Dixwell Avenue Congregational UCC, where he had served for 35 years!

Digging deeper, during his pastorate, the congregation sponsored the building of the Florence Virtue Homes, the formation of the Dixwell Housing Development Corporation, as well as sponsoring and housing within the church, the Dixwell Day Care Center and the Dixwell Children’s Creative Arts Center.Rev. Edmonds also spearheaded the development and construction of the edifice at 217 Dixwell Avenue, which was dedicated in 1970. Rev. Dr. Edmonds retired with Emeritus status in 1995.

Under his leadership, the church built a housing development and a creative arts center for the community. In addition, he was involved with many community service groups, such as the Urban League, the Association of New Haven Clergy (whose community outreach committee I had chaired in the early 1980s), the Amistad Committee, and the New Haven InterFaith Ministerial Alliance. He was also a long-time member of the New Haven Board of Education, serving as its chairman from 1979 to 1988.

Edmonds and his wife, Maye, had four daughters: Lynette Johnson, Karen Spellman, Cheryl Edmonds, and Connecticut State Rep. Toni Walker (D-New Haven). After retiring from his pastorate at Dixwell, he became a member of Church of the Redeemer UCC in New Haven.

Edmonds taught sociology at Southern Connecticut State University beginning in 1966. Even after reaching the mandatory retirement age of 70 in 1987, Edmonds continued to teach at the university by applying for special permission annually.

Even after retiring from the church in 1995, Edmonds was inclined towards continued public service. When meeting with single mothers who had to defer going to school to raise their children, he helped to establish the Edwin R. and Maye B. Edmonds Scholarship Fund for single parents.

There can be no gainsaying the fact that the Rev. Dr. Edwin R. Edmonds was a drum major for justice, fairness, reconciliation, and peace.

Project for the Beloved Community, Incorporated, founded in 1999 as MDB Ministries, Inc., is a Christian-based, nonprofit corporation that is devoted to promoting justice interpreting individual and social ethics in our society and world, and helping organizations and individuals in need of financial assistance. Whereas it is not formally a 501(c)(3) with a determination letter, it is classified as a type of church or auxiliary of a church that is automatically tax-exempt. As such, it is considered to be a 501(c)(3) organization by default and must adhere to IRS regulations, such as not engaging in political campaigns and limiting lobbying. While it is exempt from filing Form 990, donations to it are tax-deductible. At the state level, it is considered a nonprofit corporation.

If you feel compelled to make a charitable contribution to donate to the Project, you can do so by sending your contribution via PayPal (mdbwell@yahoo.com), or CashApp ($peacenik55), or Venmo (mdbwell@yahoo.com). Make sure to put “Project” in the memo. Thank you.